Strong Mayor? Why? Part 4

/The expensive push by out-of-town oligarchs to crown Kevin Johnson as “strong mayor” of Sacramento has spawned a lot of dubious arguments. But the most wrong-headed is the one being retailed by the mayor’s cheerleaders at the Sacramento Bee. Measure L is about Sacramento’s future, they tell us, “this decision should not be about Mayor Johnson.”

In fact, the strong mayor push has always been about Johnson. He and his allies started agitating to give him more power from the moment he was elected in 2008. When their first effort was ruled unconstitutional by the courts, they kept at it, until a city council majority finally agreed last year to put it on the ballot.

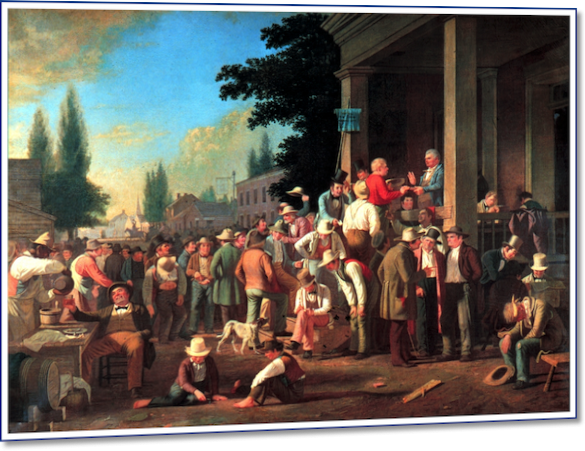

In other cities that have voted on strong-mayor measures, it’s been typical to have voters first decide whether they want a strong-mayor system, then separately elect a mayor fit to fill the newly expanded role. Not in Sacramento. Passage of Measure L would immediately give more power to Johnson.

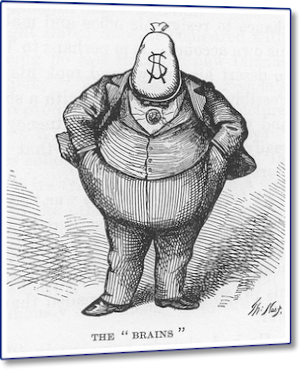

And perhaps only to him. The strong-mayor powers in Measure L go away at the end of 2020 unless voters approve them a second time. Is there anybody who believes that the coalition backing Measure L—billionaire fat cats, developers, sports owners, cops, firefighters—will be ponying up another $1 million in campaign cash to extend the strong mayor if the likely mayor after 2020 were to be a liberal environmentalist, a pension reformer like San Jose’s Mayor Chuck Reed, or a fiscal conservative opposed to welfare for sports owners and other corporate rent-seekers?

No, forget the Bee’s silly argument. Measure L is about Johnson, and nothing else. The voters’ decision about the strong-mayor system is inseparable from the question of whether Kevin Johnson is qualified for promotion to chief executive officer of the city.

What do we know about Johnson’s executive skills? His only prior management experience was running St. HOPE, a small Sacramento non-profit organization. A federal investigation by the inspector general for the Corporation for National and Community Service found that Johnson, in that management role, diverted federal grant money to personal use; illegally forced AmeriCorps members to live in and pay rent on apartments owned by Johnson’s own development company; and illegally required AmeriCorps members to campaign for his favored candidates in a local election.

On one occasion he entered the apartment of an AmeriCorps member he supervised, climbed uninvited into her bed, and put his hand under her shirt. When the young woman reported the sexual harassment to St. HOPE personnel, Johnson sent his personal lawyer to ask her to change her story and later offered her $1,000 a month to keep quiet. In the midst of the federal investigation, a St. HOPE board member was sent to delete Kevin Johnson’s e-mails from the St. HOPE computers, e-mails then under federal subpoena. The superintendent of St. HOPE’s charter schools resigned in protest of these incidents and of other mismanagement and misappropriation of funds by Johnson, as did two widely respected members of the St. HOPE school board, Bernard Bowler, a businessman, and Robert Trigg, former superintendent of Elk Grove schools.

Johnson’s record of managing his current mayoral duties follows the same pattern. A top aide stole more the $19,000 from taxpayers by charging personal items to a city credit card. The state’s Fair Political Practices Commission has fined him twice for failing to report dozens of gifts from businesses and corporate foundations to his political machine’s front groups. In 2012, as the lead city council opponent of the Measure U tax increase to balance the city budget, he was designated to write the opposing ballot argument. He forgot to submit it. “As a result, no argument against Measure U was included on the ballot,” the Sacramento County Grand Jury found.

Over the course of my career, I’ve often been involved in hiring decisions. I think it’s fair to say that on none of those occasions, in either the private or the public sector, would a candidate with Kevin Johnson’s record have been considered an appropriate choice for even a minor supervisory position, let alone chief executive officer of a $900 million-a-year enterprise with more than 4,000 employees, the position he is seeking with Measure L. In fact, hiring a manager with that record would likely be seen in court as recklessly negligent, putting at risk both the property of shareholders and the safety of employees.

And it’s also fair to say, I think, that the same standards would apply to hiring at the companies of the oligarchs funding the Measure L campaign. Theft of public funds, political corruption, sexual harassment of employees, coverup, neglect of oversight and rules—that’s not the résumé you want to send when you apply for a management job at Apple, Disney, Bloomberg, or even the Sacramento Bee.

So here’s the question that hangs in the air, unasked by the media and unanswered by the oligarchs behind Measure L: If you would never hire someone with Kevin Johnson’s sleazy record to manage your own businesses, why do you insist he’s good enough to manage our city?