Start with the formal name of Measure L itself: the Checks and Balances Act of 2014. The phrase “checks and balances” is meant to give voters a warm glow, evoking dimly remembered school civics lessons about wise men in powdered wigs writing the U.S. Constitution.

But if you paid full attention in class, or follow the news, you understand that the checks-and-balances systems in federal and state constitutions notoriously put up obstacles to “getting things done.” And with good reason: The framers of the Constitution were more concerned about restraining power than enabling action.

The system they created frequently results in divided government. A president of one party vetoes the agenda of the party that controls Congress, while the party that controls Congress tries to undermine the agenda and legitimacy of a president of the opposite party. Sometimes, even when a president and Congress get something done, a Supreme Court controlled by their adversaries barrels into the fray and strikes it down. Our history tells of long periods when federal and state governments sat paralyzed in the face of big problems, and of moments when even day-to-day activities like budgeting become occasions for crisis—think federal government shutdowns, state-issued IOUs, and the collision between President Obama and the Republican House that brought the nation to the edge of default.

Measure L invites the same gridlock in city government. Under Sacramento’s current charter, a mayor and four members of the city council can pass ordinances and a budget. It takes five members of the council, a majority, to block what a mayor wants or set a different course. Under Measure L’s “checks and balances,” a mayor would have to win over five of eight members of the council to get anything done, and it will take six of eight members of the council, a three-fourths supermajority, to pass a measure the mayor opposes.

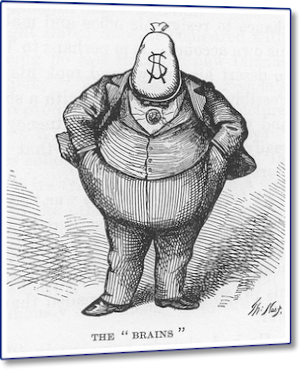

No wonder the oligarchs talk abstractly of “checks and balances.” Telling voters that they want to make Sacramento city government more like Washington probably isn’t a winning argument.

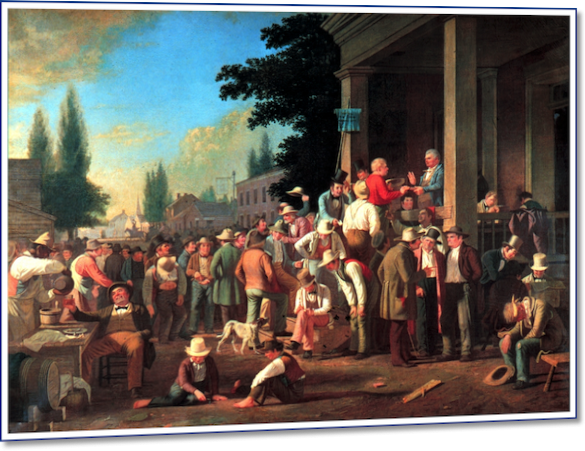

There’s a big irony in hearing today’s rich and powerful tout a strong-mayor/council government as more efficient than the council/manager model. Because a century ago, it was the very same social group, the rich and powerful, the corporate barons of America’s first Gilded Age, in partnership with newly organized chambers of commerce and a growing class of college-educated professionals, who drove the creation and spread of the city-manager form of government that the rich and powerful now want to dump.

They sought, and often won, changes in city charters to take power away from mayors and councilmen, transfering it to unelected professional city managers. The elected city officials of that day were too parochial for the oligarchs’ taste. Typically drawn from the ranks of local leaders like shopkeepers, artisans, and contractors, they won election by steering services and jobs to their voters and protecting their constituents, many of them immigrants, from the assaults on their religions and pleasures being launched by nativists and prohibitionists. They were focused on neighborhood, not the broader city-wide investments corporations wanted.

“Reformers loudly proclaimed a new structure of municipal government as more moral, more rational, and more efficient and, because it was so, self-evidently more desirable,” the historian Samuel P. Hays writes. Trained city managers, freed from patronage and politics, would deliver more honest and efficient services and attend to city-wide interests instead of neighborhoods and working-class needs. Sacramento adopted that system in 1921.

And now the heirs and successors of those oligarchs say their ancestors got it all wrong. A strong mayor will bring more efficient government.

The political scientists and economists who’ve compared the two systems disagree. They’ve found that whether a city has a strong mayor or council/manager government does not change how much it spends and taxes, how it spends its money, or how efficiently it delivers police, fire, and sewer services. As one study summarized the research, “There is no apparent difference in the efficiency levels of the two municipal government structures.”

The verdict? Judged as a spur to efficiency, the case for “strong mayor” is weak and unproven.

Next: Does having a strong mayor make a city more responsive and accountable?